Today’s education prepares people for jobs that are on the way out. If you’ve recently received an email written by artificial intelligence or been chauffeured by a machine, you see what we’re up against. As Andrew Yang notes in The War on Normal People, this will affect not only occupations obviously slated for the chopping block, like those of drivers and retail workers. It will also displace white-collar workers, from doctors to accountants.

These jobs feel real: companies fill them and governments subsidize them, but the conditions that created them are gone. Echoes of a world now passed, these jobs will soon seem as quaint as that of the telegraph operator, as machines take up routine tasks throughout the economy. Others will be more like the bank teller: we still have them, but we have a lot more ATMs.

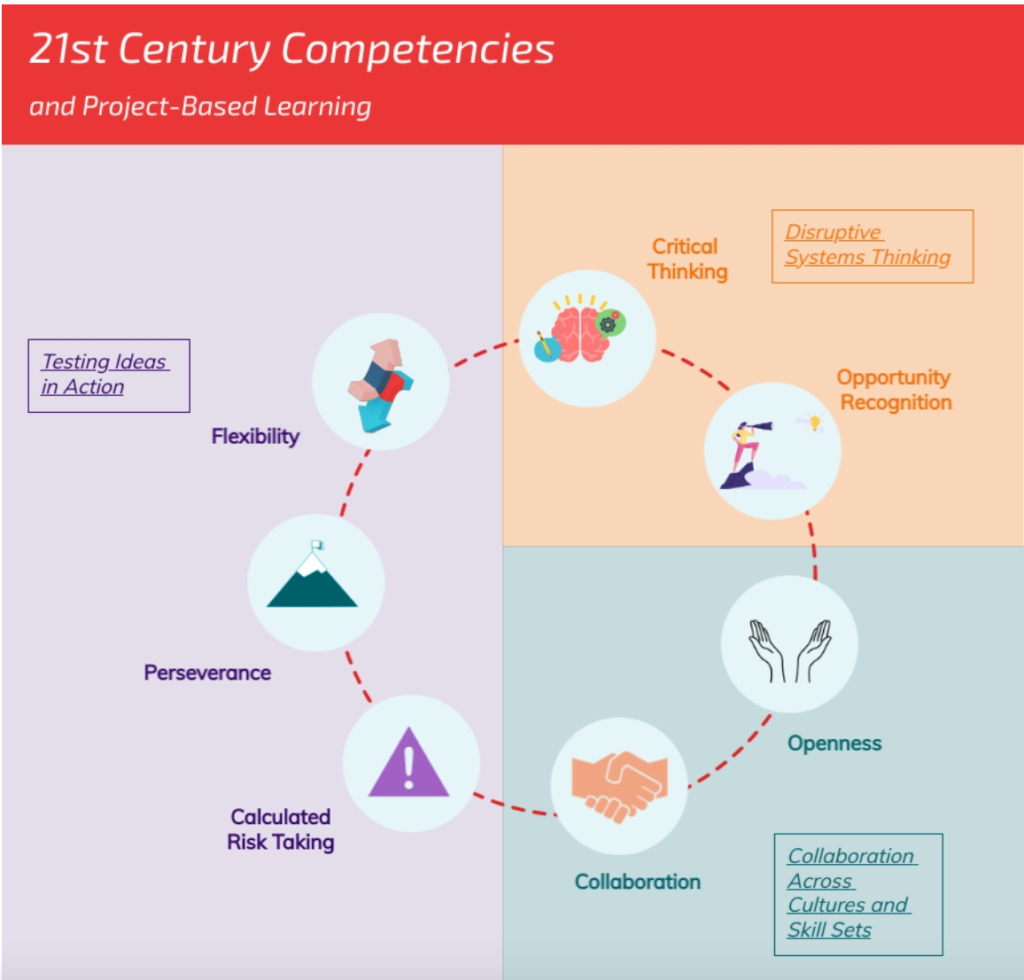

The growth opportunities for today’s grads demand that we retrain our brains. Take a look at the 21st Century Competencies depicted below. How many of these can one attain listening to an old man talk? How many can be demonstrated by picking the right answer on a test? Don’t get me wrong: I love long-dead authors and their insights as much as anyone, but I also know my students must forge solutions for which there’s no blueprint, and I don’t feel right about sending them out into the world with both hands tied behind their backs.

It’s easy to be deceived by what I call “ghost industries.” These ghost industries persist in familiar form, shielded for a time while multiple disruptions, from decarbonization to remote work, converge around them. But the more we try to shield ghost industries and obsolete jobs, the harder we make the fall when it comes. This is a story we’ve seen before. If you’ve ever passed the husks of an industry disrupted out of existence or seen what happens to a place where folks lack meaningful opportunities, you know what’s hurtling towards us. As the reorganization of work and life proceeds, to compete will require reinventing products and supply chains, business models and processes, the systems on which civilization runs.

This could spell opportunity for talent. When a generation must reinvent everything, the capability to launch and refine new experiments becomes sought-after. When industries demand innovation up and down the organization and across functions and geographies, the capacity to collaborate on diverse teams to test and scale new systems becomes paramount.

Indeed, regions, schools, and companies that equip a broad base to refine new solutions will thrive. Those that provide the structure to do this systematically, with the (virtual) “space” to build practiced capacity, will quickly outpace competitors relying on top-down or one-off models for innovation. Those who make it normal for people who see what doesn’t work to launch experiments of their own will leave innovation management consultants and platforms for the usual suspects in the dust.

Sadly, today’s schools and early careers continue to train talent to stay in one’s lane and perform established routines. Grads see where this falls short. According to a 2019 Gallup poll of grads across disciplines, “graduates who strongly agree that they participated in a project that took a semester or more to complete were more than twice as likely (41% vs. 19%) as others to strongly agree that they obtained important job-related skills.” This points a way forward. Make project-based learning, or PBL—the kind where teams develop real-world solutions of their own—widely accessible in education and on the job.

But there’s a challenge. Until now, schools and companies have lacked the wherewithal to provide project-based learning on a systematic basis. As a result, PBL too often depends on the brilliance of the instructor and the luck of the draw. Almost by definition, PBL cannot be made broadly available through the use of canned videos or relying on a few brilliant instructors.

In 2021 we tested an alternative across multiple countries. The goal was to test whether structured projects could be enabled, for a broad base of talent around the world, through what Bard’s Eban Goodstein, who has launched a global certificate for leading change within and outside existing organizations, calls a “project-based MOOC.” In this demonstration study, participants used a digital platform to pursue intensive projects. They worked through structured modules, confronting real-world challenges, and responding to constructive criticism by experts and peers.

What we learned was striking. Of course, these early results are based on participant self-reporting, and need to be followed with rigorous research. At the same time, what young people around the world tell us is noteworthy. Overwhelmingly, they say that after collaborating on project-based experiments, using a structured platform to build solutions with no blueprint, they make crucial leaps in skills and mindset. Even this preliminary research points the way for companies, schools, and regions to get out ahead of looming disruption and prepare a generation for the future of work.

We’d value your insights. If you know of an organization prepared to make the leap, please don’t hesitate to tell us.

— Alejandro Crawford, CEO, RebelBase and Professor of Entrepreneurship, Bard MBA in Sustainability

21st Century Competency Framework

To test our thinking, we gave students a structured experience developing new solutions, and then evaluated their gains using a novel competency framework we developed for the purpose. We then collected data from participants to understand whether the experience helped them develop the skills and mindset to effect change.

Teams used the modules of the RebelBase platform to identify problems and opportunities and tackle them through the projects they built. They refined their experiments by working their way through the program modules, which included activities from prototyping and testing to making the case to resource providers.They also incorporated feedback on each module from peers, instructors, and industry and community partners. This process challenged them to go beyond their initial ideas, to stress-test solutions with users and against incumbent solutions.

We surveyed them about the experience and what they took away from it, then analyzed their responses using the competency framework. This framework examined critical thinking, typically emphasized in the liberal arts, alongside opportunity recognition, more commonly associated with business training. Similarly, we looked at teamwork not merely through the lens of business efficiency but instead with an emphasis on learning from diverse disciplinary and cultural perspectives. We categorized this into three broad competency areas:

- – Disruptive Systems Thinking

- – Collaboration Across Cultures and Skill Sets

- – Testing Ideas in Action

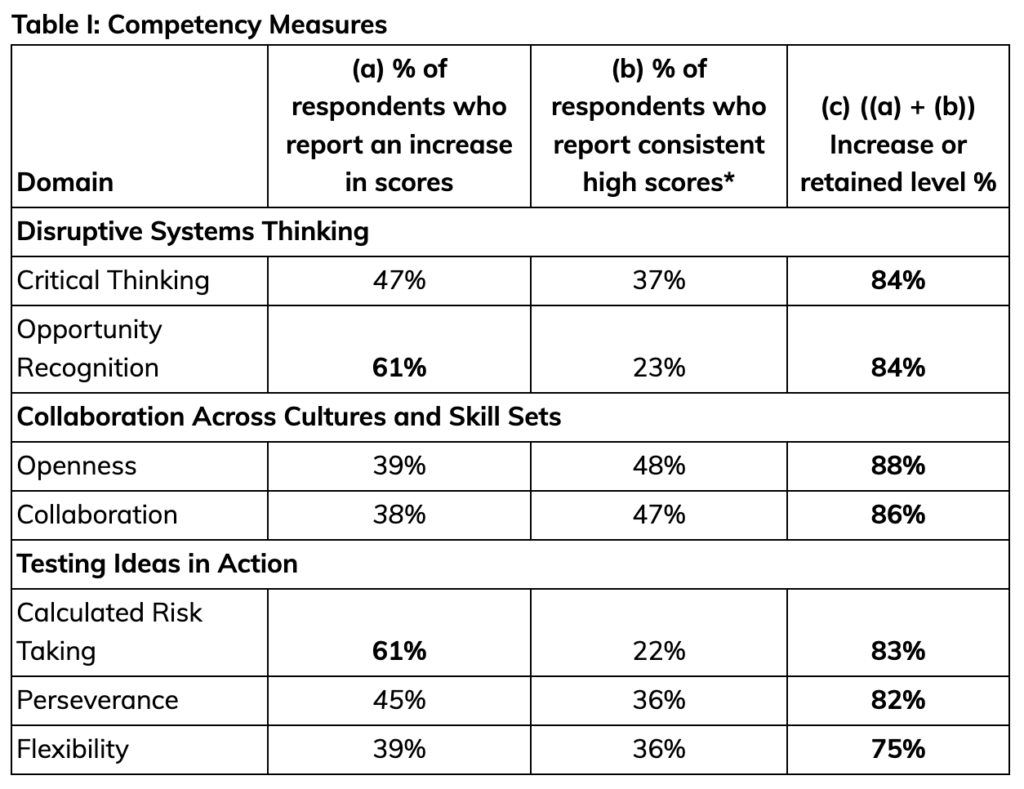

Respondents were asked to rate their growth in each area by answering a series of retrospective questions (these questions ask participants to reflect on their experience and on how this experience impacted them). Since some respondents come into the program with a high level of perceived competency in certain areas, we looked both at gains and at sustained high levels of competency.

More than four-fifths of respondents either made leaps or retained high levels of competency in key areas. Eighty-four percent (84%) of respondents say they gained or retained a strong capacity to recognize opportunities in business and social innovation, where others might see barriers. Another 84% report that they made leaps or had preexisting strength in critical thinking, defined as the capacity to comprehend social, economic, and political behavior by breaking down ideas in a way that allows for unbiased and informed decision-making. When it comes to calculated risk-taking, the capacity to assess the risks and rewards associated with key decisions, 83% say they either made leaps or started out strong. Eighty-six percent (86%) report that they gained or retained the capacity to bring diverse skills and backgrounds to produce innovative thinking in a group or on a team. (In the final case, almost half say they started out with strong collaboration abilities). Table I shows gained and retained high scores across the key competencies in the framework:

*These are participants who come into the program saying they are already confident in this area and continue to be so after the program.

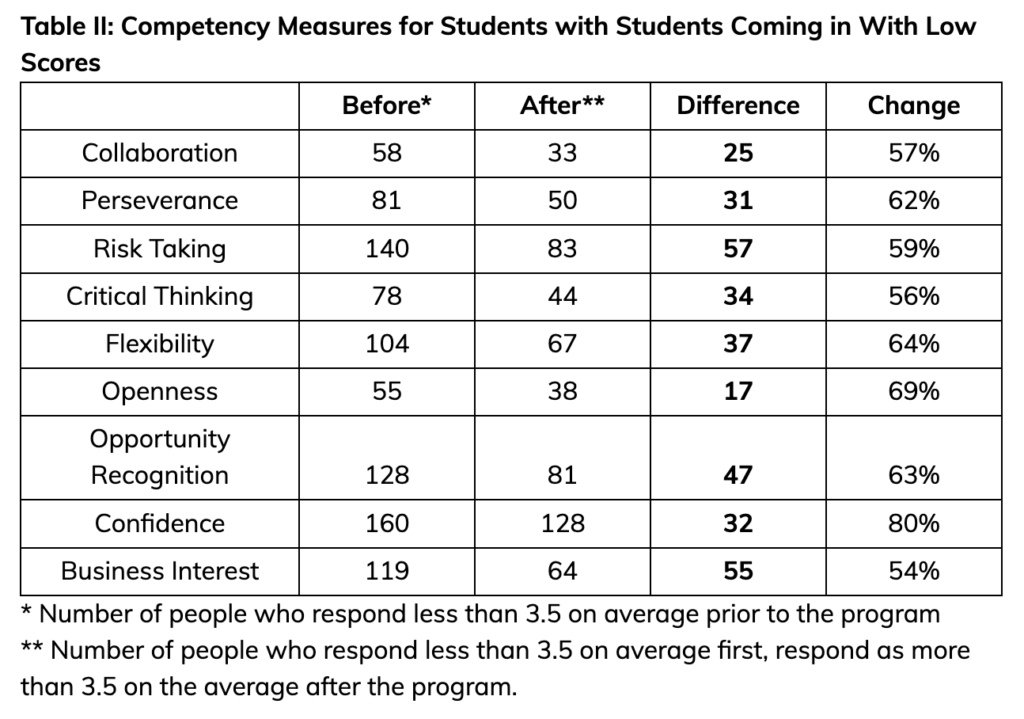

We saw considerable growth in participants who came into the program with lower-than-average perceptions of their competencies. These participants demonstrated above-average growth rates across all competency areas, particularly perseverance, flexibility, openness, and opportunity recognition.

Assessments of Entrepreneurial Confidence

Does undergoing the challenge of fleshing out a solution and submitting it to various tests increase or decrease entrepreneurial confidence? According to participant self-reporting, large majorities emerge from structured, experiential challenges in what it would take to produce a solution of their own, with as-high or higher confidence in their capacity to do so. Seventy-four percent (74%) report increases, while a full 88% report sustained or retained high confidence). This is an area in which we would be eager to compare the experience of participants to that of a randomized control group.

We examined not only confidence but also interest. Eighty-two percent (82%) report that their interest increased or sustained after completing the program using RebelBase.

We also saw a relationship between a change in the confidence or interest in entrepreneurship and perceived growth in specific competencies. For example, the 50 participants who started the program with strong confidence in entrepreneurship also demonstrated growth in terms of critical thinking, opportunity recognition, perseverance, flexibility and calculated risk-taking by the end of the program.

Eighty-three percent (83%, or 175 of 210 respondents) sustained or increased their interest in starting a new business or new initiative or launching an innovation, also demonstrated growth in terms of: collaboration, critical thinking, openness, perseverance, flexibility, opportunity recognition, and calculated risk-taking. The 91 participants who said they had a strong interest in starting a new business, initiative or innovation at the beginning of the program also demonstrated growth in terms of opportunity recognition, calculated risk-taking, critical thinking, and perseverance.

Assessments of Entrepreneurial Knowledge

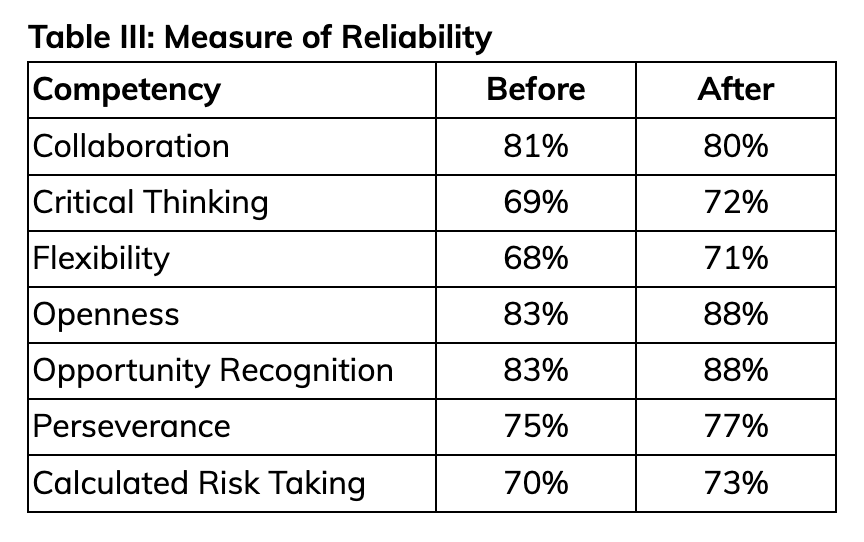

We utilized the Cronbach alpha ratio to check internal consistency and reliability in survey data. Cronbach alpha is a measure of internal consistency based on the correlation between assessment items. It shows how closely a set of questions relate to each other within a group or construct. It is used to see if the multiple Likert scale survey questions can reliably measure a certain construct.

The rule of thumb for interpreting alphas for Likert scale questions is that 70% and above is acceptable, whereas 80% and above is good.

In survey data, questions that ask participants about their mindset prior to and after participating in the program are grouped as “Before” and “After” questions. Collaboration, Openness, and Opportunity Recognition have good internal consistency, and all items have acceptable consistency.

We also asked participants to report on areas of greatest growth. The top three areas participants selected are:

- – Identifying a value proposition

- – Presenting/pitching an idea in front of a group

- – Creating an effective team

The areas in which participants perceived themselves to have grown the least are building an MVP and navigating a financial model. This result was not entirely surprising given that participants, particularly undergraduates, are often new to these more technical aspects of entrepreneurship. In addition, participants in entrepreneurship programs may struggle with financials if they lack a background in accounting or statistics.

Conclusions and Next Steps

What does this research tell us about project-based learning and the capacities it builds for meeting today’s demands? These findings provide suggestive evidence that using a structured platform for project-based learning can build skills and mindset crucial for a changing workforce. This provides a basis for future studies using a comparison or control group.

It also helps frame questions for further inquiry. For example, participants report making larger leaps in risk-taking and opportunity recognition than in flexibility and openness. Further study should isolate the reasons for these differences and assess to what extent they derive from the methodology used in the program, the time spent on various activities, and other factors.

At the same time, this suggests opportunities to improve learning tools, content, and format—and opportunities to learn from interactions with the platform itself. To more effectively capture experience and performance among participants, employees, entrepreneurs, and others using the platform, we are building a system for analyzing data to improve outcomes for participants. We’re interested, for example, in questions like iteration of a module in response to feedback and revision of inputs in one module based on learnings from another. This information can be used to add useful nudges within the platform and inform the activities of facilitators for facilitated use cases. Through analyzing the resulting data, we can further refine the methodology for effective, scalable project-based learning to prepare graduates to reinvent existing systems and compete in the future workforce.